Hanukkah and Nature: The Menorah Psalm

Don’t let anyone tell you Hanukkah is a “minor holiday.” I know, it’s been given a bump because it’s close to Christmas, and it is a Rabbinic holiday, meaning it doesn’t have some of the strictures of Biblical holidays like Passover, Shavuot or Succot, but it is as deep and meaningful as any holiday that you can name.

The light of the menorah in Jewish imagination has often been connected with Torah. Light is a universal symbol of wisdom. The light of Torah, the living wisdom that is the center of our Jewish spiritual journey, is represented in the menorah, which was at the center of the ancient Temple. If we understand the Hanukkah story as more than a political battle, but also as a spiritual battle, we can imagine that our ancestors needed to preserve something essential about the Torah in the face of enticing and modern Greek wisdom. There is nothing wrong with Greek philosophy, and the rabbis of old did, in the end, integrate a lot of Hellenism. But before they could do so, they needed to draw a line: Torah has something that is different from Greek philosophy, and in order to integrate with integrity, we needed to make sure our essential Torah wasn’t lost.

The key to understanding the difference is in the shape of the ancient Menorah. It is in the shape of a tree. (Rabbi Arthur Waskow has written about the tree image in the Menorah, and I encourage you to check out his Green Menorah Covenant.) The Israeli botanist, Noga Reuveni, identifies the Salvia Palistina plant as the possible model for the Menorah.

|

Like a tree, the Torah is alive and dynamic. We say that the Torah is eternal, but its eternity is not, like the Platonic Forms, in its unchanging, stable nature, but in its being constantly renewed. The term “ner tamid” (Eternal Light) really means “the light that is constantly renewed” because it was re-kindled constantly, every day (see Exodus 27:20).[1]

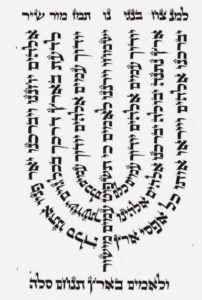

But, even more amazingly, some biblical poet turned the Menorah into actual Torah text, in what is known as the Menorah Psalm. Psalm 67 has a literary structure that is exactly in the pattern of the Menorah in the Temple. There are seven verses, with three sets of parallel branches, surrounding a central verse. This psalm has become a common element in Jewish sacred art as a part of the Shiviti texts that are often placed on the eastern walls of homes and synagogues. The Kabbalistic and numerological references are plentiful, based mainly on various permutations of the number seven (besides the seven verses there are also 49 words, but that’s only the beginning). But for now, I want to just note the meaning that can be found in its basic literary structure.

The two outside branches (verses 2 and 8—the title is verse 1, but it doesn’t count) are about blessings. The beginning verse (v.2) is deeply reminiscent of the Priestly Blessing (Numbers 6:22-27), and some say that this psalm is a completion of that blessing. It speaks of the blessing and love that starts between a particular people, Israel, and God. The last verse (v. 8) is also about blessings, but this time for the entire world. The next, more interior, set of branches is about the land. The first of the pair (v.3) speaks of knowing God’s ways, and the second (v.7) about the land giving its abundance. The most inner pair (v.4 and 6) are exact repetitions: “Peoples will praise/thank/acknowledge You, O God, all peoples will praise/thank/acknowledge You.”

The repetition drives home the importance of gratitude as we approach the central verse of the palm (v.5). This verse, cradled by gratitude, speaks of the joy of all the nations as God’s guidance brings about fair and equal judgement across the world. It is, perhaps, a vision of peace (as I’ve seen in the bumper sticker, “No Justice, no Peace”) parallel to the climax of the Priestly Blessing’s final blessing, “And God grant you peace.”

Putting it all together, the structure of this palm gives us a kind of road map, or eco/social theology of how to heal our world: first acknowledge the blessings, starting in your own particular community, and then in the larger world; then learn the ways of God. Here God’s name is Elohim, which has been since ancient times identified with nature (in Gematria, Jewish numerology, they are equivalent: Elohim = HaTeva). When we learn the ways of God in nature, the land will yield its abundance. The next step is for all peoples to acknowledge and feel the awe and gratitude of the Source of Life. When we get there, the world will be guided in fair and equal justice for all peoples, and there will be joy.

Given the state of our world today, it seems incredible and perhaps a fantasy. But that is why we have sacred times such as Hanukkah, in order to take our eyes off the news for a while and “re-vision” what is possible. We remember that miracles have happened and can happen again. We can start small, but small actions can sometimes have giant results.

We also learn an important meta-lesson from this psalm: that the wisdom of Torah is often in the pattern, in the set of relationships that makes a few verses into a menorah pattern, which is also a pattern of a tree. If we raise our hands into the air, we can feel that it’s also a pattern in our own bodies. The symmetry of our arms, legs and spine mirrors that of a leaf, a tree, and so many living beings. Looking for these kinds of patterns, which are found everywhere in Jewish writings such as the Torah, Mishnah and Midrash, we realize that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There is a kind of miracle in relationships in which meaning and vitality emerges in the connections.

Looking at the Hanukkah lights this year, perhaps we can also visualize the world coming together in relationships of justice, gratitude and peace. That will bring a true joy and meaning to this “minor” holiday.

|

[1] I first heard this idea from Rabbi Avraham Walfish, many years ago at the Pardes Institute in Jerusalem.